While watching football games and the World Series this month, I noticed several ham-handed television advertisements that seemed to be pitched to a fairly stupid audience.

The ads promote a television service, DIRECTV, contrasting it with cable television. There is discussion about DIRECTV's attributes contrasted with cable's supposed limitations, which is good as far as it goes, assuming it's all true.

But the real message seems more like a pitch to join the cool-kid clique at a high school. Speaking for DIRECTV is spokes-actor Rob Lowe, a handsome, polished guy who has a great house and parties with a group of hip, beautiful friends.

Contrasting Mr. Lowe is another man named Rob Lowe (that's not his name; he's an actor) who is ugly, ungainly and creepy. He of course is a cable customer. He is a loser.

What do you want to be -- a cool guy or a loser?

I'm sure the DIRECTV people think this is a humorous way to promote their product, but the commercials lay it on thick, really thick, encouraging viewers to laugh at strange people and, also, to prove they are cool like Rob Lowe by buying a particular television connection service.

If this campaign works and sells lots of DIRECTV subscriptions, I don't think it will reflect well on television viewers generally.

I pulled a couple of the ads off YouTube and posted them below. You probably don't want to see them again, but if you do, this is your chance.

With any luck, this promotion will be over soon. Then we can go back to commercials featuring average guys who are clueless schlubs and who are constantly overmatched by smart women who make the right purchasing decisions.

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

October 29, 1929 -- The Crash

Black Tuesday, 85 years ago today, has been known ever since as the day Americans lost faith in the stock market. It is seen sometimes as the beginning of the Great Depression, but in fact is probably only the most remembered signal that the American economy was on a downward trajectory.

The 1920s had been a period of fast growth following the end of World War I. People were adopting new technologies -- electrical service, telephones, radios and family cars -- and feeling good about their futures.

During those years, Americans came to believe that high growth was the new normal. The value of the Dow Jones Industrial Average grew 600 percent, from 63 in the summer of 1921 to 381 by early September 1929.

As stock values rose, more people invested, pushing prices higher. In those days, banks would lend up to 90 percent of the price of a stock to investors. Small investors piled into the market.

But there were warning signals that a bubble was forming. Real estate values peaked in 1925 and then began falling.

By the spring of 1929, steel production was declining, home construction was declining and car sales were declining. In addition, the 1928 and 1929 wheat harvests were huge and the oversupply of grain reduced prices in an economy that still had a large agricultural sector.

In March 1929, the Federal Reserve issued a warning about market froth and bank lending for stock purchases, and there was a "mini-crash" on the 25th of the month.

On October 28, 1929, the Dow dropped by 12.8 percent. The next day, Black Tuesday, brought another 12 percent drop.

Prominent bankers and industrialists invested in the stock market to shore up public confidence, which helped a little. But not enough.

What followed was a cascade of reactions. Banks called in margin loans that had been made for stock purchases. Stock sellers put their proceeds into banks, but their actions were offset by panicked depositors who, fearing bank failures, began drawing their money out of banks. The Federal Reserve flooded the banks with cash to keep the banks from failing.

Still, within a year 744 banks failed and another 1,350 suspended operations. (Remember, this was before the adoption of deposit insurance; unlucky depositors lost some to all of their money.) By the end of the 1939, 9,000 banks had failed.

And, confidence lost, the stock market decline continued.

As people worried about their financial security, they cut back their purchases. As demand for products declined, businesses laid off workers.

Because there was no tracking of employment at the time, the chart below estimates unemployment levels between 1929 and 1940.

Black Tuesday was scary, no doubt. Anytime the stock market drops 25 percent in two days is a concern.

But was the panicked reaction that followed proportionate to the event? Or was it an accelerant that turned an expected financial correction into the long, deep and very painful Great Depression?

Labels:

1929 Crash,

Black Tuesday,

Great Depression,

Wall Street Crash

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Horses of Honor

People participating in art is a big theme of mine, and so I was happy to learn of a big public art project this fall in the city of Chicago.

Called "Horses of Honor," it is the display along the Miracle Mile section of Michigan Avenue of life-sized fiberglass horse statues decorated in various themes. Local businesses, organizations and families pay for the opportunity to sponsor a horse and then arrange for it to be painted in an interesting style.

Sixty horses have been put up so far, and as many as 40 others are being staged. As the display ends, through November and December, the horses will be auctioned.

Proceeds will go to the Chicago Police Memorial Foundation, which provides aid to the families of officers who are killed or seriously injured in the line of duty. Since 1853, 562 members of Chicago's Finest have died on the job.

Chicago people and tourists get the pleasure of seeing what creative minds can do with a fun project. Since I have no plans for travel to Chicago this fall, I called several sponsoring organizations, whose representatives shared these photos with me.

For many more photos, check out the Horses of Honor page on Facebook.

Too Much Love

If there is a downside to this project, it is that people are too enthused about the horses.

Shortly after the installations began, one horse was damaged by a 25-year-old man who climbed onto its back to pose for a photograph. He was hauled off to the hoosegow and charged with three vandalism felonies.

Then, on the day of the Chicago Marathon, a family leaned against another horse to pose for their own photo. Unfortunately, they knocked the horse over, and the fall broke the horse in half. No word on whether Mom, Pop and the kids were jailed.

Several other horses have been damaged in similar situations.

I think I understand these peoples' actions. If I saw a brightly painted statue of a horse, I would assume that it was as sturdy as an actual horse. My first impulse would be to climb aboard and get a friend to take a picture.

In any event, these isolated incidents probably will not be repeated. Chicago's news media have mobilized to warn the citizenry not to get too personally involved with the Horses of Honor.

Proceeds will go to the Chicago Police Memorial Foundation, which provides aid to the families of officers who are killed or seriously injured in the line of duty. Since 1853, 562 members of Chicago's Finest have died on the job.

Chicago people and tourists get the pleasure of seeing what creative minds can do with a fun project. Since I have no plans for travel to Chicago this fall, I called several sponsoring organizations, whose representatives shared these photos with me.

|

| Integra Graphics by artist Vic Vaccaro |

|

| Erie-LaSalle Body Shop by its in-house artists |

|

| Chicago Speedway and Rte. 66 Raceway by Don McClelland |

|

| 24Seven Talent by Dawn Korman |

|

| Brasserie by LM by Kevin Riordan |

|

| Harry Caray's 7th Inning Stretch by C.J. Hungerman |

|

| Radisson Blu Aqua Hotel by Jake Merten |

Too Much Love

If there is a downside to this project, it is that people are too enthused about the horses.

Shortly after the installations began, one horse was damaged by a 25-year-old man who climbed onto its back to pose for a photograph. He was hauled off to the hoosegow and charged with three vandalism felonies.

Then, on the day of the Chicago Marathon, a family leaned against another horse to pose for their own photo. Unfortunately, they knocked the horse over, and the fall broke the horse in half. No word on whether Mom, Pop and the kids were jailed.

Several other horses have been damaged in similar situations.

I think I understand these peoples' actions. If I saw a brightly painted statue of a horse, I would assume that it was as sturdy as an actual horse. My first impulse would be to climb aboard and get a friend to take a picture.

In any event, these isolated incidents probably will not be repeated. Chicago's news media have mobilized to warn the citizenry not to get too personally involved with the Horses of Honor.

Monday, October 27, 2014

The Raptor Trust

The Significant Other and I took advantage of a gorgeous fall day recently to visit the Raptor Trust in Millington, New Jersey. It's a small place, not heavily trafficked and deeply peaceful.

The facility was established more than 30 years ago as a bird rescue site by Len Soucy, who announced recently that his son would take over the organization. The 2013 annual report noted that 3,509 of our feathered friends had found their way to the trust's "repair shop for wrecked birds" last year -- hawks, owls, falcons, vultures, eagles and ospreys, as well a large number of orphaned songbirds.

Most of the birds had been found on roadsides or injured in collisions with human structures. Those that can be treated or just need a little time to grow to maturity are released. The birds whose injuries are more severe are given long-term leases on the site.

Here are a few of the birds we saw.

|

| A curious kestrel |

| A barred owl, one of several |

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Peter Max and Corvettes

Sports car collectors have been all atwitter the last few days following the announcement that artist Peter Max's collection of Corvettes -- one for every year from 1953 to 1989 -- are coming out of storage and being given long-deferred maintenance. They will be released on the market soon.

Here are a couple of Max's 1968 vintage posters that you can buy at petermax.com.

Mr. Max has continued to make art since then, but his 1960s work defined him and his subsequent pieces reflect a similar orientation.

Born Jewish in Berlin, Mr. Max and his family fled the Nazis, and he was raised in Shanghai and Haifa, Israel.

It surprised me to learn that he collected iconic American sports cars, since he reportedly does not have a driver's license.

Plus, there is nothing I have observed in his work, then or since,that suggests an interest in things mechanical.

I do not possess a photo of the Peter Max Corvette collection, but if you are curious, a quick online search will turn up pictures of very, very dusty cars that have been sitting, unused and unmaintained, in garages for 25 years.

Corvette History

By the 1950s, sports cars were popular in Europe, but there had never been a lasting American model. In 1951, an engineer at General Motors began plumping for the company to produce a snazzy two-seater. Not surprisingly, the engineers and executives of America's largest automotive company -- all car guys themselves -- liked the idea very much and were eager to diversify beyond the familymobiles that had been Detroit staples for, well, forever.

The initial plan was to use stock frames and motor elements and top them with a sporty exterior, all to be marketed at about $2,000, then the average price of an American car.

Thus the Corvette was cobbled together, given its name, and introduced as a concept car in January 1953 at a Motorama display in New York. Reaction was great. Eventually, 300 Corvettes were sold that year at a price 50 percent higher than was first anticipated. All were white convertibles with red interiors and black canvas tops.

The first Corvette was not a fast, well-engineered car, but because so few were built, their value has only grown. If you want to buy one now, it will cost you several hundred thousand dollars.

By 1963, Corvette sales totaled more than 20,000 units for the first time. Over the years, the car had grown sleeker with a more powerful engine, and there were coupe and convertible models. The sports car had arrived in America.

Over the next two years, Porsche began marketing its popular 911 sports car in the United States.

A nice 1963 Corvette, if you can find one, would fetch anywhere from $45,000 to $250,000.

Advertisements of the car in 1973 pitched it not just as a cool car but an aspirational one. It had become a prototypical all-American guy car; 30,464 were sold.

By 1978, perhaps in response to increased competition, Corvette commemorated its 25th anniversary -- "men, machines and memories" -- and, I think subliminally -- its American tradition.

Sales just kept increasing -- to almost 47,000 units in 1978 -- but so did the competition. There were the Datsun (now Nissan) Z cars; British Jaguars, MGs and Triumphs, and a new Porsche, the 928.

The next 10 years were not glory years for Corvette. An auto blog, edmunds.com, called five Corvettes released between 1979 and 1988 among the "Ten Worst Corvettes of All Time."

These cars in the Peter Max collection are not expected to be worth a great deal, especially after the maintenance required after they have sat for 25 years in garages.

I still don't have an idea why Mr. Max collected all those Corvettes. He doesn't seem to have regarded them as investments. It makes me suspect that he may have other unsuspected collections of Americana that will be uncovered in the coming years. Those, too, would be something to see.

Corvettes Today

I am not a sports car enthusiast, but reading about Corvettes made me curious. It seems that the 2014 edition has been well received. A driving review is posted below

Here are a couple of Max's 1968 vintage posters that you can buy at petermax.com.

|

| "Dove," $1,260 |

|

| "The Different Drummer," $1,660 |

Mr. Max has continued to make art since then, but his 1960s work defined him and his subsequent pieces reflect a similar orientation.

Born Jewish in Berlin, Mr. Max and his family fled the Nazis, and he was raised in Shanghai and Haifa, Israel.

It surprised me to learn that he collected iconic American sports cars, since he reportedly does not have a driver's license.

Plus, there is nothing I have observed in his work, then or since,that suggests an interest in things mechanical.

I do not possess a photo of the Peter Max Corvette collection, but if you are curious, a quick online search will turn up pictures of very, very dusty cars that have been sitting, unused and unmaintained, in garages for 25 years.

Corvette History

By the 1950s, sports cars were popular in Europe, but there had never been a lasting American model. In 1951, an engineer at General Motors began plumping for the company to produce a snazzy two-seater. Not surprisingly, the engineers and executives of America's largest automotive company -- all car guys themselves -- liked the idea very much and were eager to diversify beyond the familymobiles that had been Detroit staples for, well, forever.

The initial plan was to use stock frames and motor elements and top them with a sporty exterior, all to be marketed at about $2,000, then the average price of an American car.

Thus the Corvette was cobbled together, given its name, and introduced as a concept car in January 1953 at a Motorama display in New York. Reaction was great. Eventually, 300 Corvettes were sold that year at a price 50 percent higher than was first anticipated. All were white convertibles with red interiors and black canvas tops.

The first Corvette was not a fast, well-engineered car, but because so few were built, their value has only grown. If you want to buy one now, it will cost you several hundred thousand dollars.

By 1963, Corvette sales totaled more than 20,000 units for the first time. Over the years, the car had grown sleeker with a more powerful engine, and there were coupe and convertible models. The sports car had arrived in America.

Over the next two years, Porsche began marketing its popular 911 sports car in the United States.

A nice 1963 Corvette, if you can find one, would fetch anywhere from $45,000 to $250,000.

Advertisements of the car in 1973 pitched it not just as a cool car but an aspirational one. It had become a prototypical all-American guy car; 30,464 were sold.

By 1978, perhaps in response to increased competition, Corvette commemorated its 25th anniversary -- "men, machines and memories" -- and, I think subliminally -- its American tradition.

Sales just kept increasing -- to almost 47,000 units in 1978 -- but so did the competition. There were the Datsun (now Nissan) Z cars; British Jaguars, MGs and Triumphs, and a new Porsche, the 928.

The next 10 years were not glory years for Corvette. An auto blog, edmunds.com, called five Corvettes released between 1979 and 1988 among the "Ten Worst Corvettes of All Time."

These cars in the Peter Max collection are not expected to be worth a great deal, especially after the maintenance required after they have sat for 25 years in garages.

I still don't have an idea why Mr. Max collected all those Corvettes. He doesn't seem to have regarded them as investments. It makes me suspect that he may have other unsuspected collections of Americana that will be uncovered in the coming years. Those, too, would be something to see.

Corvettes Today

I am not a sports car enthusiast, but reading about Corvettes made me curious. It seems that the 2014 edition has been well received. A driving review is posted below

Saturday, October 25, 2014

Buster Posey in Georgia

The San Francisco Giants are now down, 2 games to 1, in their third World Series of the last five years.

Nobody is counting the Giants team out, however, not least because of its catcher, no-drama Buster Posey, who is a formidable hitter and, increasingly, the leader and heart of the team.

|

| Courtesy of the Lee County Ledger |

Posey grew up in a small town, Leesburg, Georgia. Some combination of his personality, his upbringing and the traditional values of his home town seem to have formed him into the careful, modest, driven athlete whom parents would like their children to emulate.

I have friends and family in southwest Georgia, one of whom shared some Buster Posey lore.

"The local legend is that when he was in T-ball, with his father as coach, he kept hitting balls off the tee until even his father was too tired to pay attention," she said. "I have heard that he used to hit 500 -- some say 1,000 -- balls each day when he was four or five years old, that he 'wanted' to hit that many balls."

Posey's high school baseball coach was quoted saying this: "Most want to practice the things that they already do well. The difference with Buster is that he wanted to work on the things that aren't as much fun, where he really needed to improve."

Posey is the oldest of four children. His sister, Samantha, was a standout softball player at Valdosta State, and his brothers both played Division 1 baseball.

When Posey was called up by the Giants, his father told an interviewer, "I still think Sam is the most athletic of the (children.) She has the most tools. Buster, I think he's just the hardest worker."

Buster Posey's awards and stats are impressive. He was college baseball catcher of the year and the National League Rookie of the Year in 2010. After spending most of 2011 recovering from a serious early-season ankle injury, he came back in 2012 to win the NL MVP. His batting average is consistently over .300, often way over .300.

"This is a very humbling game," a teammate once said. "A lot of times people come in with a lot of flash, and the game humbles you and you play a certain way. But Buster came in playing that way. For him, it's not about back flips or hoopla or loudness or grandstanding. It's about standing in the box and hitting a grand slam in the playoffs and acting like 'that's what I should do with that pitch.'"

Leesburg, Georgia

Posey retains his connection to his hometown. He married his high school girlfriend, and they have a place in the area where they spend time with their twin children. In the off-season, he can be found working out at the local YMCA. He is seen sometimes at church with his grandparents.

When he won the MVP in 2012, Posey was not available for the traditional award ceremony. He already had committed himself to be the guest speaker at a fundraiser for the school where his mother teaches. He gave one of the MVP prizes, $10,000 in Louisville Slugger merchandise, to his high school team and has contributed money for larger projects there as well.

Leesburg is a small town, about 3,000 people. It has 12 churches, chapters of the Sons of the Confederacy and the NAACP, civic organizations including the Moose, the Masons, the Lions, the Key Club, the Vietnam Veterans of America, a Women's Club and a Pregnancy Resource Center.

A couple years ago, Forbes magazine named Leesburg as the second best place in Georgia to raise a child, and I think there is something to that.

Last year, I went with a friend into a store in a larger town nearby. The store owner and my friend recognized each other but couldn't exactly place where they had met. My friend mentioned her church, and he said no, he was a member of a different congregation. She talked about the tutoring program she ran for poor children, and he said, no, his group sponsored children's art fairs. She mentioned that her husband was member of a particular Kiwanis group, and he said he belonged to a different Kiwanis group.

These people were very involved in their community. Where I live, this doesn't happen so much. When I read about alienated young people who turn to terrorism or go on shooting rampages, I wonder about these things.

Other Leesburg Luminaries

Two music stars also hail from Leesburg.

One, Phillip Phillips, won the American Idol competition in 2012. He just released his second album. The other, Luke Bryan, was the American Academy of Country Music Entertainer of the Year in 2013.

Like Posey, they are alumni of Lee County High School. Earlier this year, Bryan took a Parade reporter on a tour of Leesburg. "It was black, white Mexican," he said. "We'd all go out in the schoolyard and break-dance.

"I loved growing up here."

Friday, October 24, 2014

The Government Wants You to Buy a House

This bit of folk wisdom was shared with just about every young adult who came of age and got a steady job between 1945 and 2006. Yesterday, we discussed the antecedents of this policy.

It was based largely on the fact that mortgage interest expense can be deducted from AGI in federal income tax filings.

It made a certain sense. During much of that period, the American economy was growing and new households were forming. Home prices generally followed suit, increasing as well.

But during the 1990s, the government doubled down on promoting home ownership for everyone. This may have been a reaction to the despicable practice of redlining -- withholding credit from low-income and/or minority people, refusing to offer home loans in poor neighborhoods -- but once it got going, the effort took on a life of its own.

First Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the national mortgage insurance providers, were incentivized with credits to offer more loans to poor people. Then the agencies reduced down payment requirements for loans. Then they reduced the personal credit history requirements for borrowers. Then they blessed increasingly strange adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). Early in the aughts, some government programs even gave people cash toward down payments on home purchases.

And it wasn't just the government. Mortgage origination offices were eager to write up the contracts and collect origination fees. Wall Street bankers were happy to bundle the loans and sell them as bonds, also collecting fees. Ratings agencies rode along, issuing indefensible opinions that the new loans were secure and would be repaid, again for fees. Real estate agents loved the increased volume of business and the new transaction fees they collected. Everybody was in on the game.

By 2005, according to the National Association of Realtors, almost half of new homebuyers made no down payment at all when buying houses. Another 20 percent made down payments of less than 5 percent. Houses were effectively being given away on the promises of increasing incomes and increasing home values.

The census chart below shows the effect on national home ownership.

As might be expected, this had other effects. With many more people able to buy houses, price competition raised home prices. The higher demand for houses led builders to construct many new subdivisions, especially in areas where land was cheap.But during the 1990s, the government doubled down on promoting home ownership for everyone. This may have been a reaction to the despicable practice of redlining -- withholding credit from low-income and/or minority people, refusing to offer home loans in poor neighborhoods -- but once it got going, the effort took on a life of its own.

First Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the national mortgage insurance providers, were incentivized with credits to offer more loans to poor people. Then the agencies reduced down payment requirements for loans. Then they reduced the personal credit history requirements for borrowers. Then they blessed increasingly strange adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). Early in the aughts, some government programs even gave people cash toward down payments on home purchases.

And it wasn't just the government. Mortgage origination offices were eager to write up the contracts and collect origination fees. Wall Street bankers were happy to bundle the loans and sell them as bonds, also collecting fees. Ratings agencies rode along, issuing indefensible opinions that the new loans were secure and would be repaid, again for fees. Real estate agents loved the increased volume of business and the new transaction fees they collected. Everybody was in on the game.

By 2005, according to the National Association of Realtors, almost half of new homebuyers made no down payment at all when buying houses. Another 20 percent made down payments of less than 5 percent. Houses were effectively being given away on the promises of increasing incomes and increasing home values.

The census chart below shows the effect on national home ownership.

Many people, unsophisticated in real estate, began buying homes and flipping them every year or so. They assumed the prices would just keep rising, even though the economy and people's incomes were not increasing at a similar pace. Others bought homes in fear that prices would go so high that they would be unable to buy ever again.

The strategy worked -- until it didn't.

By 2006, the frothy real estate market had hit a wall. Housing prices had become too expensive for just about everybody. The people who had been planning to flip their houses and collect nice gains found themselves stuck.

In addition, people who had taken out some of the nutty ARM loans were unable to pay their mortgages when the early years' teaser rates expired and interest expense was adjusted to the market rate.

By the time the economy went into recession in 2007, house prices had begun to collapse. People who could not afford their homes began to default. Mortgage bond payouts declined rapidly, taking financial institutions with them. Many people discovered that their homes were worth less, sometimes much less, than the mortgage notes they had signed, and that there were no buyers willing to pay enough to get them out from under their debt.

Here are a couple charts that demonstrate the macro effects. The second one demonstrates that home ownership still remains relatively more expensive than renting. Both suggest that, even with the dip that followed the housing collapse, the price of homes didn't adjust downward as much as should have been expected and that another bubble might be developing.

The fallout of the housing crash echoed through the economy. A savings and loan I knew a bit (but whose stock I did not buy) served as an illustration to me.

The S&L was founded in California in the middle of the last century. It was careful, conservative and profitable until the founders retired and the son-in-law of one took over. It was seized in 2008 and sold to a bigger bank. At the time, $6.9 billion of its assets were in "option ARM" loans that allowed borrowers to choose how much to pay each month; most payments were not covering even the interest expense on their mortgages, with the result that mortgages were growing as home values were declining. The S&L also had gone big on "reduced documentation" loans, known as liars' loans because borrowers' credit and asset claims were not checked before loans were approved. By the end of 2005 more than 90 percent of the S&L's mortgage originations were of the "reduced documentation" variety.

The fate of such lenders was bad, but the worst pain was for the people who lost their homes.

In May of last year, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis issued a report concluding that Americans had built back only 45 percent of the assets they lost in the 2007-2008 recession.

"While many Americans lost wealth during the Great Recession," CBS quoted the bank president as saying, "younger, less-educated and nonwhite families lost the greatest percentage of their wealth."

According to CBS, "Those families tended to have low savings and high debt."

Today: The government still wants people buy houses.

Current FHA requirements for loan guarantees require only 3.5 percent down payments, even if the entire down payment consists of gifted money, usually from families. In addition, the FHA will insure loans for borrowers with credits scores as low as 500 (the scale is 300 to 850) "so long as there's a reasonable explanation for the low FICO (credit score.)"

The "Welcome Home Illinois" program provides $7,500 toward a down payment for those with incomes up to $88,320. Buyers are required to ante in 1 percent of the purchase price or $1,000, whichever is greater. First-time buyers and people who have not owned a home in the last three years, with incomes up to $88,320, are eligible.

In New York, the Smart Move program requires a 1 percent down down payment and offers a second mortgage at a low interest rate for a total of 99 percent financing to homebuyers with incomes of $83,400 or less.

There has been discussion lately suggesting that, post recession, lenders have tightened mortgage requirements too much. That may be. I hope these government-assisted homebuyers are able to keep their houses and that the homes they buy increase in value. After the experience of the last 10 years, though, I worry.

Labels:

Fannie and Freddie,

Great Depression,

Home Ownership,

Housing Bubble,

Housing Policy,

Mortgages

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Home Ownership for Everyone? A History

For as long as I can remember, owning a home has been taken for granted as an essential element of the American Dream. But this may be a relatively recent aspiration, arising only in the second half of the last century. Let me tell the story in two parts.

Early in the Century

In the 1920s, fewer than half of American families owned their homes. American financial institutions offered two ways to finance such purchases:

-- from banks, which required a 50 percent down payment and offered five-year loan terms,

with balloon payments required to cover final payment at the end. It appears that many

people, perhaps most, renegotiated their mortgages frequently and avoided the big final payment.

-- from savings and loans, which required smaller down payments of 30 to 40 percent, and

offered self-amortizing notes that paid off loan balances over 11 or 12 years.

These were pretty onerous terms. Saving between 30 percent and 50 percent of a home's purchase price must have been a heavy burden in times when people were much poorer and innovations like electricity and indoor plumbing still were far from common in American houses.

During the 1920s, the American economy caught fire. Stock prices rose and rose, as did home prices. By 1930, 46 percent of American families owned their homes, and home values had increased substantially, creating what we would now call a bubble.

We all know what happened in the 1930s. The stock market crash of 1929 was followed by a breakdown of the economy. Millions of people lost their jobs and the money they had invested in the stock market. Banks, at least the ones that survived, pulled back and refused to renegotiate their five-year balloon notes. Not surprisingly, the housing bubble burst, and home values dropped by half.

In 1938, the government established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) to guarantee longer-term home loans at fixed rates and keep people in their houses. This no doubt helped, but by 1939, 10 percent of all homes were in foreclosure and the rate of home ownership had dropped to 42 percent.

World War II and Later

The real estate market stayed flat through the Depression and World War II. When employment picked up to manufacture weapons and other supplies for the troops, jobs became more plentiful, but there was not much to buy. Everything from nylon stockings to gasoline and tires, from cigarettes to canned food and coffee and sugar was rationed. All workers were urged strongly to buy war bonds.

After the war, the soldiers came home, and the demand for housing for new families grew exponentially, assisted by the newer, government-guaranteed mortgage model of 80 percent fixed-rate loans that amortized over 30 years.

This worked pretty well until it didn't. A recession in the early 1970s and several other events -- an oil price spike, runs on the dollar and the government's easy money policies -- raised interest rates so high during that decade that homes and home loans became much more expensive.

According to the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), the average interest rates on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage increased from around 7.5 percent in 1971 to 12.88 percent in early 1980. Here was the effect on typical families.

1971 1980

Median Home Price $25,200 $62,900

Median Family Income $7,805 $16,154

30-Year Monthly Pmt $186 $481

Mortgage/AGI 29% 37%

Even with the increase in mortgage costs as a portion of family income, the percentage of homeowners grew slightly over the period, from 64 percent in 1971 to 65.5 percent in 1980. Much of this no doubt reflected the coming of age and family formation during that period of the Baby Boom generation, the largest in American history.

Still, homeownership increased from 42 percent in 1939 to almost two-thirds by 1980. Then things got really interesting. More on that tomorrow.

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

A Quiet Day

The Idiosyncratist is taking a day off to think. I do not have a well-thought-out post for today and do not wish to waste the time of my kind readers. Going forward, I plan to post five times weekly, not seven, so as to maintain quality standards and also keep up with other demands in my life.

My very best wishes to you all.

My very best wishes to you all.

Monday, October 20, 2014

The Death of Klinghoffer

The most controversial opera of modern times -- The Death of Klinghoffer -- opens tonight at New York's Metropolitan Opera House in Lincoln Square.

The work has been performed many times, but the Met's staging is seen by people who deplore it as giving Klinghoffer the opera world's equivalent of a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. The objections are that the piece is anti-Semitic and that it promotes sympathy for terrorists.

The opera's story, probably fresher in people's minds when it debuted in 1991, is based on the 1985 hijacking of a Mediterranean cruise ship by Palestinian terrorists who shot Leon Klinghoffer, a disabled Jewish man in a wheelchair, and dumped his body into the sea.

The opera opens with a prologue of two choruses. First comes the "Chorus of Exiled Palestinians" who are run out of their homes in 1948 after the establishment of Israel. Then comes the "Chorus of Exiled Jews" who leave Europe after the Holocaust to settle in the new Israeli state.

There is beautiful music in this opera, including the Hagar Chorus, directed below by the opera's composer, John Adams.

Hagar, you will recall from the Bible, was the servant of Abraham's wife, Sarah. Hagar bore Abraham's son Ishmael, whose descendants became the peoples of the Middle East. Abraham and Sarah's son, Isaac, was the father of the Jewish tribes.

In effect, the opera asserts the inextricable linkage of Palestinians and Jews. It depicts Palestinian terrorists as human beings with their own story and frustrations and motivations.

After 9/11, this is a hard sell for Americans.

Former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani and several politicians of both parties plan to lead a protest today. The current mayor, Bill De Blasio, has decried European anti-Semitism but defended the opera. "The American way is to respect freedom of speech," he said. "Simple as that."

A First Amendment lawyer, Floyd Abrams, penned a newspaper opinion piece arguing that the opera certainly deserved protection as free speech. But, he asked, would the Met mount an opera justifying the frustrations and hatred of the killers of John F. Kennedy or Martin Luther King, Jr., or of the 9/11 airplane bombers?

"One can argue passionately about the Middle East, Israel or Palestinians," he wrote, "but nothing makes the Klinghoffer murder morally tolerable."

The Met responded to critics by canceling a planned telecast of the opera and also its radio broadcast. The opera's playbill will include a statement from Klinghoffer's children, who denounced the opera after watching its first performance in 1991.

John Adams in turn denounced the Met. "The cancellation of the international telecast is a deeply regrettable issue and goes far beyond the issues of 'artistic freedom,' and ends in promoting the same kind of intolerance that the opera's detractors claim to be preventing," it said.

In fact, a part of the opera depicting an American Jewish family, friends of the Klinghoffers, was seen as offensive caricature and removed from the piece long ago.

Below are the two prologue choruses from a 2003 movie of the opera by a British filmmaker. The music and the libretto are not the issue, but the images accompanying the music strike me as heavy-handed. The film was well-received around the world, but not so much in the United States, where it was not widely shown.

The film critic for the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that "the combination of artistic sophistication and moral obtuseness that has characterized The Death of Klinghoffer is ratcheted up to new levels in this repulsive film version."

A critic from the site Film Threat called the movie "an unashamedly pro-Palestinian and virulently anti-Israel (and, unspoken but clearly implied anti-American) creation."

Other songs and choruses from Klinghoffer also can be found on YouTube. I do like the choruses.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

The Boys in the Boat

I'm a reading a book that you might enjoy. It knits several elements -- a remarkable personal story, the fellowship of athletes, observations on life and sport and global tensions 80 years ago -- into a readable narrative that holds my attention and is pulling me right along.

The book is The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown, who discovered almost by accident that a neighbor of his had been part of a remarkable rowing team at the University of Washington in the early and mid 1930s.

The neighbor, Joe Rantz, had a difficult youth. After his mother died and his father remarried, Joe was basically abandoned in the early days of the Depression. Resourceful, honorable, hard-working and very, very poor, he found his way to the University of Washington and onto its rowing team as a member of an 8+, a scull with eight rowers and a coxswain who called the pace.

Here are a couple things I've learned along the way in this remarkable story:

-- The popularity of competitive rowing in years past.

In 1934, almost 80,000 people came to watch a UW regatta with the University of California, Berkeley, at Lake Washington; many thousands of others, in both states, followed live event reports on the radio.

The Intercollegiate Rowing Association's regatta, on the Hudson River near Poughkeepsie, N.Y., attracted as many 125,000 spectators each year.

Sports writers and broadcasters of the day covered rowing competitions as they now do football and basketball, although apparently paying attention to crews instead of individual athletes.

-- The challenge of competitive rowing, and its beauty.

"Physiologists, in fact, have calculated that rowing a two-thousand-meter race -- the Olympic standard -- takes the same physiological toll as playing two basketball games back-to-back. And it exacts that toll in about six minutes," writes the author.

The sport commands "the perfectly synchronized flow of muscle, oars, boat and water; the single, whole, unified and beautiful symphony that a crew in motion becomes -- is all that matters."

The idea of committing oneself, all in, to the perfection of a focused, demanding, cooperative effort is so compelling that I almost wish I had gone out for crew myself when I was in college. We all want to be part of something bigger than ourselves.

But the book is about more than that.

It sets the Washington team -- rowers, coaches and the philosophical woodworker who built the most efficient sculls in the world -- in the difficult days of the Depression with broader sketches of hardship across the United States during those years.

It follows the group's ups and downs as it tackles its elusive and challenging ambition to row in the 1936 Olympic games held in Berlin, then ruled by a darkening Nazi regime that planned to use the games to promote its malign devotion to the idea of Aryan superiority.

It follows the group's ups and downs as it tackles its elusive and challenging ambition to row in the 1936 Olympic games held in Berlin, then ruled by a darkening Nazi regime that planned to use the games to promote its malign devotion to the idea of Aryan superiority. The pursuit of the Olympic goal drives the book forward. The interwoven story of one rower's hard life and gallant perseverance adds personal interest that keeps the reader turning the pages.

The Boys in the Boat was released in May and now is available on Kindle for only $2.99.

.

Saturday, October 18, 2014

Taxis and the Next New Thing

New York City's taxi system, like many others, has been for generations a well-protected one. Periodically, the city auctions off small numbers of taxi medallions -- essentially the right to operate a single cab -- at prices of $1 million or more.

Over time, this has resulted in less than ideal results for taxi customers. There have not been enough taxis in the city -- particularly in the outer boroughs -- and a politically motivated group, the medallion owners, have fought to keep things that way. Who needs competition?

One example of the problem has been the sad fact that there are 20 percent fewer taxis on Manhattan streets during evening rush hour than at any other time of the day.

In 2004, the city attempted to address the situation by adding a $1 surcharge to taxi fares between 4 p.m. and 8 p.m. on weekdays. Seven years later, a New York Times article explained that this had not worked:

"The hour from 4 to 5 p.m. has long been considered the low tide of taxi service, the maddening

moment when, in apparent violation of the laws of supply and demand, entire fleets of empty

yellow cabs flip on their off-duty lights and proceed past the outstretched hands of office

workers seeking a ride home."

It turned out that cab drivers worked 12-hour shifts and changed shifts in the late afternoon, dropping their cars at stations located outside expensive Manhattan. When it was suggested that the shift could be changed earlier -- say at 2 p.m. -- second-shift drivers objected because they did not want to miss the lucrative 2 a.m. rush of drinkers seeking cabs after bars closed each night.

So when taxis were most needed, the industry preferred not to be there.

There were other problems -- reluctance to pick up minority passengers, the illegal adjustment of rate calculators to assess higher charges, drivers taking naive tourists on roundabout routes from airports into the city -- that were just accepted as part of the system.

In short, you could say the taxi industry was not customer-facing.

Destructive Innovation

So in came ride-sharing companies that offered an alternative to traditional taxicabs.

Using well-designed cellphone apps, rideshare companies allow would-be taxi patrons to hail private cars. When riders contact these rideshare companies, the apps locate nearby drivers, specify where riders want to go, negotiate and collect fees for trips and notify riders when their cars will arrive, even tracking the cars as they approach.

The rideshare companies are very lean operations. They do not own cars but merely match private drivers with those seeking rides. After deducting a portion of each fare, they transfer money to the driver, who receives a 1099 for tax purposes at the end of the year. The companies also track and make available passengers' and drivers' ratings of each other, providing some quality-control information before rides are signed up.

There are now a number of these companies -- DiscountCab, Sidecar, Gett, Zimride, Ridejoy, Hailo, Uber and of course Lyft, which is best known for placing silly pink mustaches on the grills of its cars.

Not surprisingly, the traditional taxi regimes are fighting back. City taxi regulators raise safety and liability concerns, all in the interest of protecting the riding public. Taxi companies have tried to enlist government in banning rideshare companies. Taxi drivers in Europe have been particularly aggressive in fighting the new operators.

Change is never easy.

The Battle for Market Share

The rideshare industry is new, but it already is consolidating. Hailo recently pulled out of the North American market altogether after two years of failing to establish significant market share.

Various of the companies are fighting to get governments to grant them exclusive rights to send cars to airports to pick up and drop off passengers.

In January, the small rideshare company Gett charged that Uber employees had ordered and then cancelled 100 Gett rides in a three-day period and that Uber had tried to convince Gett drivers to join the Uber network.

Several months ago Lyft charged that Uber employees engaged in a similar effort involving false credit card numbers and the ordering of 5,500 rides that were then cancelled, often after a Lyft driver had arrived to pick up a passenger.

Uber has countercharged that Lyft has done the same thing.

These companies aren't competing for customers. Each is trying to drive the other out of the market and to create a monopoly.

So far, Uber is the biggest company in the rideshare space. It is valued at $18 billion and probably is looking to mount an IPO. Pretty good money for a cellphone app.

It also is getting involved in government, as taxi companies used to do. Recently it hired David Plouffe, who previously worked as a congressional aide and campaign strategist. NPR's story on the hiring carried the headline, "Uber Greases the Wheel with Obama's Old Campaign Manager."

The Washington Post explained why Uber hired an expensive fixer.

"Uber is the latest Silicon Valley heavyweight to discover that tech disruption requires

overcoming political and regulatory barriers. The past 20 years have been littered with

examples of companies, from Microsoft to Apple to Facebook, learning, often late, that

they must play in politics to continue to grow."

Plus ca change, plus c'est la meme chose.

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

Stories from the Flu Pandemic

|

| from flu.gov |

In the fall of 1918, a flu pandemic swept the world. In the United States, an estimated 25 percent of the population fell sick and 675,000 people died.

Curiously, the youngest were among the most vulnerable, particularly young adults. Older Americans seemed to have acquired a certain immunity during an earlier flu season before the turn of the century.

In 1918, doctors believed the flu was a bacterial infection. In fact, it was a virus, but viruses were little understood at the time. The distinction made no difference: There were no medicines in 1918 to treat infections of either kind. Treatment consisted of rest, aspirin and patent medicines.

People retreated to their homes. Public gatherings were cancelled, many schools were closed and church attendance stopped for several months. Cities including San Francisco required everyone to wear gauze masks in public and jailed those who did not wear such masks. In retrospect it was revealed that gauze masks offered little if any protection.

|

| A New York mailman, from archives.gov |

Family Stories

There are a few oral history sources of people's memories of the 1918 flu. I culled the quotes below from flu.gov and historymatters.gmu.edu. They are lightly edited but intact in substance.

From Pennsylvania:

-- "My grandmother had a separate room curtained off when seven of their children got sick with the pandemic flu. When she entered the room, she wore gauze over her nose and mouth. Of the seven children that got sick, four of them died . . . . My aunt said that she knew when one of them was not going to live because her mother would sit with the child in the family's rocking chair and sing to him/her. The rocking chair would creak and when it stopped, she knew they were gone."

From Missouri:

-- A younger daughter stayed home in December 1918 when her parents and older siblings went for a sleigh ride. Afterward, "all four children caught the flu; all four died within one week. It was so cold they put the bodies outside. Before he died, one of the boys said to 'just put me outside, I will join the others in a few days.'"

From South Carolina

-- "My grandfather William, a merchant, met his wife Lily at a church gathering. They had five children, three boys and two girls. William registered for the draft but was not called to serve. His business was very prosperous and became more so when the flu epidemic began -- due to increased demands for his livery (taxi) service. As soldiers returned home with the flu, William picked them up from the train station. As the numbers of flu stricken soldiers grew, he stopped charging for this service.

"Sadly William contracted the flu and died in January 1919 at the age of 38. Lily never remarried and life was very hard for the widowed mother and their children."

From South Carolina

-- "My grandfather William, a merchant, met his wife Lily at a church gathering. They had five children, three boys and two girls. William registered for the draft but was not called to serve. His business was very prosperous and became more so when the flu epidemic began -- due to increased demands for his livery (taxi) service. As soldiers returned home with the flu, William picked them up from the train station. As the numbers of flu stricken soldiers grew, he stopped charging for this service.

"Sadly William contracted the flu and died in January 1919 at the age of 38. Lily never remarried and life was very hard for the widowed mother and their children."

From Kentucky, a 95-year-old coal miner's memories:

"And every, nearly every porch that I'd look at had -- would have a casket box sittin' on it. Men were a diggin' graves just as hard as they could and the mines had to shut down there wasn't nary a man, there wasn't a mine arunnin' a lump of coal or runnin' no work. Stayed that way for about six weeks."

-- Above is the burial site of an entire family lost: two parents and their children aged 19, 16, 10, 8 and 4 years old. (The family name was misspelled on the tombstone.)

A Nurse's Story

Nurse Carla R. Morrisey wrote an article, "The Influenza Epidemic of 1918," that is part of the Navy Department Library. In it, she recalls what she was told by her great aunt, also a nurse, of caring for sick sailors at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois. Here are some excerpts:

"With a room of 42 beds and twice that many sick sailors, Josie often worked 18 hours a day. 'As the boys were brought in we would put winding sheets on them even if they weren't dead. You would always leave the left big toe exposed and tag it with the boy's name, rank and next of kin.' As one boy lay dying in bed, one waited on a stretcher on the floor for the bed to empty. Each morning as the ambulance drivers would bring in more sick boys they would carry the dead bodies out. Josie often said she felt sorry for the poor boy on the bottom. . . . As the weeks dragged on the truck loads of caskets left daily for the train station to destinations listed on the 'tag' as next of kin.

"Nursing was nine-tenths of the battle in recovering from influenza. Since there were only palliatives for the flu and pneumonia it developed into, doctors were not the essential ingredient in fighting the disease . . . . Josie would work endless hours trying to relieve the high fevers and nosebleeds before the lungs filled with blood and face turned blue."

Conclusion

There have been many advances in medical treatment since 1918. Vaccines and retroviral medicines have taken most of the sting out the flu. Polio vaccinations, developed in the early 1950s, eradicated a childhood disease that killed thousands and paralyzed many thousands more in the United States, including an American president. Worldwide, polio has been defeated almost everywhere.

On the whole, we are much healthier than people in 1918, but other challenges -- malaria, chikungunya, Ebola, Lyme disease -- are with us. With time, new diseases are sure to arise.

A Nurse's Story

Nurse Carla R. Morrisey wrote an article, "The Influenza Epidemic of 1918," that is part of the Navy Department Library. In it, she recalls what she was told by her great aunt, also a nurse, of caring for sick sailors at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois. Here are some excerpts:

"With a room of 42 beds and twice that many sick sailors, Josie often worked 18 hours a day. 'As the boys were brought in we would put winding sheets on them even if they weren't dead. You would always leave the left big toe exposed and tag it with the boy's name, rank and next of kin.' As one boy lay dying in bed, one waited on a stretcher on the floor for the bed to empty. Each morning as the ambulance drivers would bring in more sick boys they would carry the dead bodies out. Josie often said she felt sorry for the poor boy on the bottom. . . . As the weeks dragged on the truck loads of caskets left daily for the train station to destinations listed on the 'tag' as next of kin.

"Nursing was nine-tenths of the battle in recovering from influenza. Since there were only palliatives for the flu and pneumonia it developed into, doctors were not the essential ingredient in fighting the disease . . . . Josie would work endless hours trying to relieve the high fevers and nosebleeds before the lungs filled with blood and face turned blue."

Conclusion

There have been many advances in medical treatment since 1918. Vaccines and retroviral medicines have taken most of the sting out the flu. Polio vaccinations, developed in the early 1950s, eradicated a childhood disease that killed thousands and paralyzed many thousands more in the United States, including an American president. Worldwide, polio has been defeated almost everywhere.

On the whole, we are much healthier than people in 1918, but other challenges -- malaria, chikungunya, Ebola, Lyme disease -- are with us. With time, new diseases are sure to arise.

Monday, October 13, 2014

The Pandemic That Started Here

The most frightening diseases humans have faced have come from many places.

The Black Plague, which reduced the population of Europe by one-third in the 14th century, is believed to have been transmitted to humans by fleas from Central Asia.

The SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic that killed 8,100 in 2002 was passed to humans by small mammals in the Guangdong Province of China.

Ebola, which was first traced to fruit bats and then other animals, has arisen several times in Africa since 1976.

Interestingly, the most deadly pandemic of modern times, the misnamed Spanish Flu of 1918, is now believed to have originated in a rural county in the American Midwest.

The Spanish Flu in Context

The world rejoiced in November 1918 when World War I ended. In its four years, more than 20 people, military and civilian, lost their lives. But an even worse killer was still on the loose.

During 16 weeks at the end of 1918, a vicious flu spread across oceans, among combatants and ordinary citizens, through cities and and countries worldwide. After four scant months, between 50 million and 100 million people -- no one can say for sure -- died and the virus went to ground and disappeared.

Where the Flu Began

|

| Camp Funston Flu Patients, 1918, from the U.S. National Archives |

-- A British scientist suggested the origin was WWI British Army post in France where

doctors treated "purulent bronchitis" in 1916, but this theory was dismissed because

the disease had not rapidly or broadly as the flu had done.

-- Another flu outbreak in early 1918 in China was studied but seemed unlikely because

it stopped early and did not spread far.

-- Several other outbreaks of disease in early 1918 in France and India also were ruled out

for similar reasons.

All the signs pointed to origination in the United States where, Barry wrote, "One could see influenza jumping from Army camp to camp, then into cities, and traveling with the troops to Europe."

Gene sequencing of preserved tissue suggested that the outbreak was very rapid. Epidemiological studies and oral histories narrowed the focus to Haskell County, Kansas, a rural area with a population of 1,720 and an economy based on farming grains and raising poultry, cattle and hogs.

In early 1918, the local doctor observed many cases of influenza. Barry's article noted the following:

"Soon, dozens of his patients -- the strongest, the healthiest, the most robust people in

the county -- were being struck down as suddenly as if they had been shot. Then one

patient progressed to pneumonia. Then another. And they began to die . . . . The

epidemic got worse. Then, as abruptly as it came, it disappeared. Men and women

returned to work. Children returned to school. And the war regained its hold on people's thoughts."

The doctor's warning, sent to national public health officials, was the first alarm sounded anywhere in the world. By that point, the end of March, the flu had run its course in Haskell County but just begun its spread.

At the time, the U.S. Army was preparing recruits for service in Europe. Haskell County soldiers were trained at Camp Funston, home to more than 56,000 troops. Starting on March 4, soldiers at the camp started coming down with the flu; 1,100 were hospitalized and many others were treated at infirmaries.

The soldiers transferred from Camp Funston to other Army bases and then to France. According to Barry, "by the end of April twenty-four of the thirty-six main Army camps suffered an influenza outbreak. Thirty of the fifty largest cities in the country also had an April spike in excess mortality from influenza and pneumonia."

The flu proceeded from there. Its second wave, later that year, was far more deadly.

Barry's conclusion:

"The fact that the 1918 pandemic likely began in the United States matters because it tells investigators where to look for a new virus. They must look everywhere."

Sunday, October 12, 2014

The Portland Building

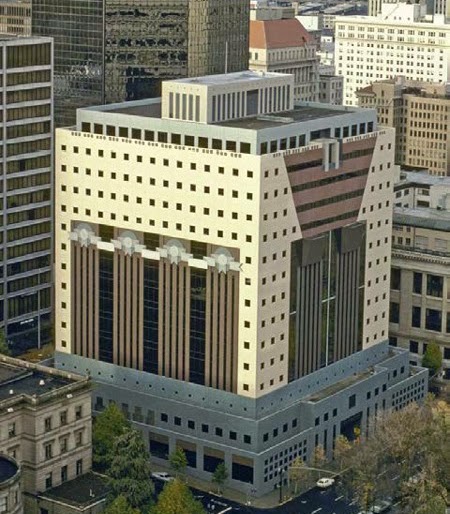

Above is a photograph of the Portland Building, a 1982 construction that was labeled the first post-modern building in the country. It houses 1,300 civic employees in Portland, Oregon, and now the city fathers have a decision to make about it -- whether to fix the darn thing or tear it down and start over again.

If you have seen the television show Portlandia, you have seen pictures of the building and the 35-foot copper statue that looms over its entrance, as seen in the photo below.

When the city council approved construction of the building in the early 1980s, Oregon's economy was shedding jobs and money was tight. Following the design advice of starchitect Philip Johnson, the politicians approved the cheapest proposal, submitted by architect Michael Graves. His vision was a highly decorated square box painted in unusual colors. The cost was reported variously as $24 million, $25 million and $29 million.

Some people love the Portland Building. It won an American Institute of Architecture Honor award in 1983. In 2011 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

But not everybody was pleased with the result. Shortly after it opened, city workers began to complain about low ceilings and small windows that let in very little light, a constant concern in Portland's gray climate. Entrances were small and dark, unwelcoming in a city that prided itself on its downtown pedestrian culture.

Here, in the center below, is one of the finalists that was rejected. It would have cost $1 million to $2 million more than the Graves project.

The proposed building was modern, not postmodern, but it had large windows and was perched over a large pedestrian walkway area. Its design came from the well-regarded Arthur Erickson of rainy Vancouver, B.C., whose native climate perhaps made him more sensitive to the light and foot traffic concerns of a city like Portland.

Then the problems began.

Functional Issues

In a 1997 the publication Architronic ran a critique called "Michael Graves's Portland Building and Its Problems." Here is a short excerpt:

User-unfriendliness, virtually all of which resulted from clear-cut design flaws, was

only part of the problem and in the long run, perhaps the least significant. The con-

struction problems that began emerging almost immediately after the building opened

proved far more serious. From the beginning, windows leaked, floor levels undulated

so that office chairs rolled away rather than remaining in place, and salts leached from

from the exterior tiles at both the street level and in the "pilaster" above. In less than

a decade after the building opened, the entrance had to be redone to render it more

visible; at the same time the lobby and other spaces were remodeled and circulation

improved. Then, in the fall of 1995, a minor leak in the roof led to the discovery of

major structural flaws.

Earlier this year, The Oregonian, the city's daily paper, reported that Portland faced a decision: to spend $95 million on an overhaul to fix the Portland Building, to sell it (to whom was not clear) or to tear the building down and build something better at a cost of $110 million to $400 million.

Among the issues:

-- Water leaks "from just about every surface -- the roof, windows, siding, grout,"

-- Structural deficiencies that would not have satisfied Portland's 1980 seismic codes

and that appear more threatening still as earthquakes have been judged more

likely in the Northwest in the intervening years, and

-- A needed complete restoration of the building exterior.

City leaders seem to be favoring the expensive retrofits, perhaps to be financed by a bond measure to be repaid over many years.

Quotes about the Portland Building

". . . an imposing 15-story edifice that's one of the most hated buildings in America. The facade is an off-putting hodgepodge of faux classical columns and useless decorative elements, and penitentiary-like small windows with a depressing color scheme . . . . 'It's all gaudy imagery with no tie to the location,' says Jason Fifield, an associate at Ankrom Moisan Architects in Portland. The interior isn't much better -- it's described as dark and claustrophobic."

Bunny Wong,

"The World's Ugliest Buildings"

Travel and Leisure, Oct. 2009

"It's not architecture, it's packaging. I said at the time there were only two good things about it: 'It will put Portland on the map, architecturally, and it will never be repeated.' "

Pietro Belluschi,

1972 AIA Gold Medal winner

quoted by Rebecca Morris,

"30 Years of Planning

Produce City for the '90s"

The Oregonian, Feb. 19, 1990

"I can't think (of) that as being monumental. I think (Graves is) a turning point, sort of a symbol of our discontent or of our superficiality. You see, he has come to think in terms of our society nowadays, conditioned much more than we realize, by the television, by the communication media, and by all the advertising and all the fluffy, the fashionable forms which are today and . . . disappear tomorrow. It's part of our culture to have nothing lasting, nothing serious . . . . in fact, even our thinking in regard to buildings that are going to be there for a long time."

Pietro Belluschi,

Oral History Interview, 1984,

Smithsonian Archives of American Art

"It has not aged well. To be more precise: it looked like shit. . . .

"Meanwhile, across town, we have Pietro Belluschi's 1947, aluminum-clad Equitable Life Building (which) won the AIA 25-year award in 1982. . . . The Equitable Building looks timeless."

Alexandra Lange,

"Portland + Timelessness,' April 3, 2013,

The Design Observer Group

Saturday, October 11, 2014

Minimum Wage

$10.00

I think it is time to raise the minimum wage. The people who earn the current minimum wage, or a little bit more than the minimum wage, are having a hard time supporting themselves.

The federal minimum is now $7.25. Let's make it $10.00. Expensive cities and states -- San Francisco, New York -- can set higher minimums if there is local support.

People get crazy when they talk about this.

Those who support a higher minimum wage believe that evil, greedy CEOs and billionaires are getting wealthy on the backs of poor people. This is largely untrue. Most low-wage workers are employed in retail and food service establishments that run on very slim margins.

Those who oppose a higher minimum wage argue that there will be fewer jobs as a result. This probably is true. Businesses that cannot raise prices enough to generate income at this wage will close. Fast-food businesses probably will move faster than they are doing already to replace counter workers with digital ordering systems.

I prefer not to get into these arguments because they lead nowhere.

What moves me is the simple fact that we have a large working class of people who must piece together several low-wage jobs just to make ends meet. The Affordable Care Act decreed that full-time workers -- defined as those working 30 hours a week or more in a job -- must get health insurance coverage from their employers. And many business owners need higher staffing in peak hours and leaner staffs during the slower periods of the day. Effectively, it makes sense for employers to limit hours for low-skilled and easily replacable employees.

If you have the misfortune to be one of those easily replacable employees (and there are more people looking for work than there are jobs at this point), you find yourself stringing together two to four part-time jobs and traveling from one job to another -- a few hours here and a few hours there every day -- to achieve something like a 40-hour workweek, which is what used to be the definition of full-time employment.

Raising the minimum wage to $10 will allow some of these unfortunate people to cut back the number of part-time jobs they hold. For two such people who are married, 40-hour workweeks at minimum wage will generate an annual income of $40,000, which isn't great but is certainly above the poverty line.

For the rest of us, this will mean higher prices at restaurants and grocery stores, and even fewer employees in department stores.

For workers whose efforts cannot generate more than $10 an hour worth of benefit to employers, this will mean unemployment.

Those are the trade-offs.

I'd like to see a lower than 25-percent high school dropout rate. I'd like to see more training programs in high schools and community colleges. I'd like more employer- and union-sponsored internships in the skilled trades. I'd like states to drop expensive certification requirements for mid-skill jobs like hair braiding.

We can't seem to get any of these common-sense things done, unfortunately.

So, at the very least, why don't we should raise the minimum wage?

For the rest of us, this will mean higher prices at restaurants and grocery stores, and even fewer employees in department stores.

For workers whose efforts cannot generate more than $10 an hour worth of benefit to employers, this will mean unemployment.

Those are the trade-offs.

I'd like to see a lower than 25-percent high school dropout rate. I'd like to see more training programs in high schools and community colleges. I'd like more employer- and union-sponsored internships in the skilled trades. I'd like states to drop expensive certification requirements for mid-skill jobs like hair braiding.

We can't seem to get any of these common-sense things done, unfortunately.

So, at the very least, why don't we should raise the minimum wage?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)